Details

Kong Shangren (孔尚任; 1648 - 1718) was a Qing Dynasty dramatist and poet

best known for his chuanqi play The Peach-Blossom Fan (桃花扇 Tao Hua

Shan). Kong was a distant descendant of Confucius.

The Peach Blossom Fan tells the story of the love story between the

scholar Hou Fangyu and the courtesan Li Xiangjun, against the dramatic

backdrop of the short history of the Southern Ming. It remains a

favourite of the Kun opera (kunqu) stage.

This luxury edition is a reproduction of an illustrated edition of the

late Qing Dynasty. The 44 illustrations are by artists with unknown

identity. Beside the original text by Kong Shangren, summaries in modern

Chinese and English to the 40 scenes of the drama are added.

Abstract from the Preface

The transition from one dynasty to another is always a painful

experience to the subjects of the former regime. The intellectuals in

the early Qing dynasty were no exception. On the one hand, the fond

memory of the smiles and tears of bygone years and the loyalty to their

former sovereign still lingered in their hearts. On the other hand, the

merciless fact of reality forced them to readjust themselves to a new

way of life under the new regime. Such a confliction mind is agonizing,

but it could sometimes lead to literary achievement. “Peach Blossom

Fan”, finished in 1699 and considered later as one of the four best

ancient Chinese plays, was the brainchild of such a troubled mind.

Why did the Ming dynasty fall? Particularly why was the Southern Ming

regime vanquished so quickly? The explanation of unequalled military

forces was only superficial, there surely must have been some deeper,

underlying reasons. About this, the contemporary intellectuals must have

their own opinions. But under the rule of the new regime, they could

not make their statements openly. The only way to express their piece of

mind was under the disguise of literary works. Thus, using his gifted

pen, Kong Shangren interwove the sad history of the downfall of the Ming

dynasty with a love story between Hou Fangyu and Li Xiangjun in a

40-scene kungqu drama for the stage.

Kong Shangren was born at Qufu, Shandong province, in 1648. He was a

sixty-fourth generation descendant of Confucius. At age 21, in 1669, he

became a National University Student by contributing his farmland to the

state. At age 36, in 1684, he was invited to lecture classics before

the Kangxi Emperor (r. 1662-1772) when he latter visited Qufu to pay

tribute and make sacrifice to Confucius. Kong was in the Emperor’s good

graces and was bestowed the position of Erudite of National University.

At age 38, in 1686, Kong supervised the dredging of the Yellow River

estuary under Sun Zaifeng, Vice Minister of Ministry of Work, at

Weiyang. At age 42, in 1690, he was back to the capital and accepted the

post of Erudite of National University again. At age 46, in 1694, he

was promoted to the position of Secretary of the Ministry of Revenue.

This year he collaborated with Gu Cai to write a chuanqi drama “Little

Thunderclap” (xiao hulei, a Tang dynasty stringed instrument). At age

51, he finished the drama “Peach Blossom Fan” which was started before

he was 36 years old. The play became very popular when it was put on the

stage. At age 52, he was promoted to the position of Vice Director of

Guangdong Squad in the Ministry of Revenue but was dismissed within one

month. At age 54, in 1702, he was back to his hometown at Shimenshan,

Qufu county. He died at home in 1718 at the age of 79.

It is hard for us, the nowadays readers, to understand fully the complex

feeling and sentiment of the intellectuals of the Han nationality after

the downfall of the Southern Ming regime. According to the teaching and

philosophy of Confucius, an intellectual should be loyal to his

original sovereign and his own nationality, Han. He should not accept

the reign of an alien regime. But the harsh reality showed them that

resistance was futile, that acceptance of the rule of the new regime

seemed to be the only way out, and that obedience and reconciliation

with the new rulers might bring them practical benefit. Thus, the

special historical events of the transition period between the Ming and

Qing dynasties formed the dual personality of the intellectuals at that

time. Under certain circumstances, they would heartily praise the good

deeds of the new government. But under other occasions, the memory of

their bygone and national consciousness would make them lament over

their old regime. This tendency could be seen in the drama Peach Blossom

Fan. At the beginning of the drama, Kong extolled the good management,

prosperity and peace of the early Qing dynasty. But he also praised

lavishly the loyalty and patriotism of Shi Kefa and other anit-Qing

heroes and censured harshly the corruption and villainy of Ma Shiying’s

group. The text of the play also revealed the deep sorrow and

lamentation over the falling of the former regime. Here the readers

might feel puzzled. They might wonder about the motive of the play and

the author. Are they pro-Ming or pro-Qing? Is the eulogy to the new

regime genuine? Or is the lamentation over the old regime genuine? Alas,

both are heartfelt. For the whole thing is a dilemma due to special

historical circumstance.

The stories and characters in the drama Peach Blossom Fan were based on both historical facts and fictitious imaginations.

The prototype of the heroine, Li Xiangjun, came from the “Stories of

Lady Li” in volume 5 of Zhuanghuitang wenji, The Collection of Annotated

Works of Hou Fangyu. Her real name was Li Xiang, a singing girl in

pleasure quarters by the Qinhuai river. Hou Fangyu, the hero in the

drama, alias Hou Chaozong, was a native of Shangqiu, Henan province. His

grandfather was Hou Zhipu. His father was Hou Xun. His uncle was Hou

Ke. The held respectively the positions of Chief Minister of the Court

of Imperial Sacrifices, Minister of the Ministry of Revenue, Chancellor

of the National University in Ming dynasty. They had all joined the

Eastern Forest Party. Fangyu was a very learned man with good memory

power. He was also good at composing poems and proses. In 1632, at age

15, he got his xiucai degree at the prefectural level and was highly

esteemed by Zhang Pu and Chen Zilong, leaders of the Revival Society. He

passed the county examination in 1639.

Li Xiang met Hou Fangyu in 1639. According to the Stories of Lady Li,

Ruan Dacheng, a corrupt high-rank official of the Southern Ming regime,

whom the members of the Revival Society despised, wanted to make the

acquaintance of Hou Fangyu so that he could become a liaison between

Ruan and the Revival Society. Ruan asked a certain General Wang to

contact Hou and treat him frequently with feast and wine. Li Xiang

surmised Ruan’s plot. She warned Hou that the real purpose of Wang was

and not to make friend with him. After Ruan’s plot was fully exposed,

she urged Fangyu to refuse Ruan. In 1640, Fanyu failed in the imperial

examination. Li Xiang held a small party at Taoyedu to bid him farewell.

Soon afterwards, Tian Yang, a former governor of Huaiyang District,

proposed to Li Xiang for marriage with a dowry of three hundred silver

taels. Li Xiang refused him flatly. Tian felt ashamed and was very

angry. He began to harass Hou and Li by spreading rumors. He also wrote

repeatedly censuring letters to Hou. To these, Fangyu answered in his

letter “A Reply to Sir Tian”, stating that he had not communicated with

Li Xiang since they parted in 1640, neither did not know anything about

her. Yu Huai (1616-1696), a contemporary author with Hou, stated in his

book Banqiao zaji, Miscellaneous Records of the Plank Bridge: Li Xiang

was short in stature, with fair complexion. She was clever, pretty,

amiable and quick-witted; and was lovingly nicknamed xiangshanzhui,

meaning a little pendant of a fragrance fan by her adorers. …

In the text of the drama, Ruan Dacheng forced Li Xiangjun to remarry to

Tian Yang. Xiangjun hit her head in an attempt to commit suicide. She

did not die, but her blood stained the poem fan which Hou Fangyu gave

her as a token of their love. By adding a few twigs and petals, Yang

Longyou transferred the stain into a picture of peach blossom. In

“Origin and Details of the Peach Blossom Fan”, finished in 1699, Kong

said: “My elder cousin Fangxun had been a Secretary of Justice of the

Southern Ming regime during the later days of Chongzhen period. He and

my uncle, Mr. Qin Guangyi, were the husbands of two sisters. As a

refugee, my uncle fled to the dwelling of Fangxun and stayed there for

three years. Therefore he was quite familiar with what happened during

the reign of the Hongguang regime. After returning home, he told me many

anecdotes about this period on numerous occasions. When compared with

various assorted unofficial accounts, they all confirmed the

authenticity, without any discrepancy, which shows they are all factual

records. Only the anecdote about the blood stained peach blossom was

told to Fangxun by the servant boy of Yang Longyou but not recorded in

other books. However, the story was unique and intriguing. It inspired

me to compose the drama Peach Blossom Fan in which the rise and fall of

the Southern Ming regime were interwoven with the love story of two

young people.” According to the above mentioned statement, the

blood-stained peach blossom saga must have been a true story instead of a

make-believe tale conceived by Kong Shangren after he read the Stories

of Lady Li.

There was no record about what happened to Li Xiang afterwards.

According to legend, she was selected into the inner court of Prince Fu

when he became the Emperor of Southern Ming. After the fall of Nanjing

in 1645, she fled to a nunnery at the Cloud-roosting Mountan and became a

nun under Bian Yujing, a former fellow singing girl of the Qinhuai

pleasure quarters. The next autumn she met Hou Fangyu after he escaped

from the “ten-day-massacre at Yangzhou”. Then he took her to his

hometown Shangqiu. By using a false name, Li Xiang was admitted into

Hou’s family. Fangyu participated the county examination of the Qing

regime in 1651 and travelled to the South again in 1652. Soon

afterwards, when her secret past and identity were discovered, Li Xiang

was expelled from Hou’s mansion and sent to a manor house in the suburb

where she lived in loneliness and broke down from depressed mood. She

died only at the age of 27. However, in the text of the drama, Kong

Shangren treated the story in a different way. After Yangzhou was

captured, Fangyu fled back to Nanjing and found Xiangjun. Experiencing

so much wear and tear of life, they finally realized the true spirit of

Taoism. There was no place for them to settle down, and the peach

blossom fan was torn, then they followed the Taoist way respectively.

Other personages interwoven historical events in the drama were also

based on documented materials, although some of the details might be

fictitious. For example, according the history, Shi Kefa was killed

after the fall of Yangzhou. But in the drama, he committed suicide by

drowning himself in a river. As a historical play, the inclusion of

made-up characters of fictitious details are permissible, sometimes due

to political necessity, sometimes due to the requirement of the plot of

the play. Although these fictitious writings should not be considered

genuine history, they were not the product of random imagination.

After the Peach Blossom Fan was finished, Kong Shangren could not afford

to have it printed. At first, the play was circulated through

hand-copied manuscripts. In 1708, Tong Hong travelled to Shandong and

asked Shangren for a manuscript. After reading a few lines, he praised

the work lavishly and donated 50 silver taels as the fund for printing.

Then Kong put in some additional money and the first edition of Peach

Blossom Fan was engraved. The book blocks were originally stored at

Jieantang, Kong Shangren’s former residence. It was therefore the

edition was called Jieantang edition. There were various editions

printed after the Jieantang edition. In 1957, the Commercial Press

published it as a photocopy edition in a 5-part series, A Collection of

Ancient Traditional Opera (Guben xiqu congkan wuji). In addition, there

was a pocket edition, called Xiyuan edition, which was engraved after

the Jieantang edition during the years of Kangxi Emperor (r. 1662-1772).

There were more than one reprinted editions. One of them was Lanxuetang

edition printed in 1895. It was actually a reprinted edition after the

Xiyuan edition. Soon afterwards, there was an edition attached with the

Stories of Lady Li. In 1919, “A Collection of chuanqi Drama” was printed

by Nuanhongshi of Liu Shiheng (1875-1926) of Guichi. It was an edition

with fairly good collation, and the 30th book of this series was Peach

Blossom Fan. This edition was published later as a photocopy edition by

Guanglin guji keyinshe in 1979 and in 1990 respectively.

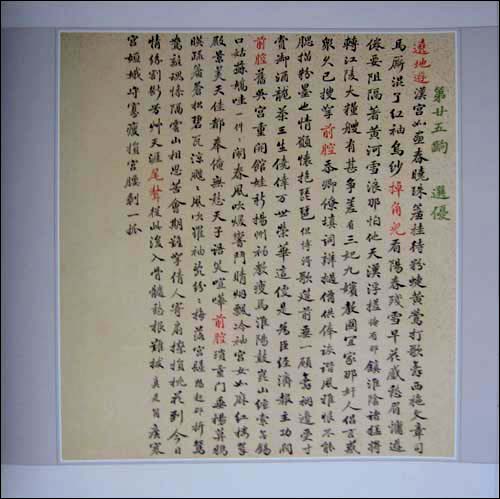

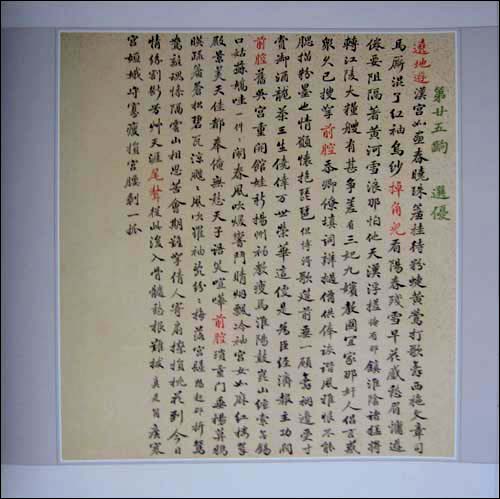

The phototype we photocopied here is the only colored-illustrated

edition of “Peach Blossom Fan” in China. It is now housed in Peking

University Library. The story of how it was passed from one master to

another is also very mysterious, it was closely related with nearly the

entire history of the Qing dynasty.

There are 4 additional scenes in the drama “Peach Blossom Fan” besides

the 40 scenes. They are, namely, Prologue, Supplementary Scene 20,

Prologue to Scene 21, Continued to Scene 40. The album contains 44

pictures, each of them depicting the typical plot of one scene. There

are not many characters in each picture, but each of them is vivid and

life-like. The background sceneries were designed with beauty of

simplicity. The excellent penmanship and the elegant coloring of the

pictures indicate that the album is really a masterpiece. It is very

interesting that although the characters and sceneries of the pictures

were based on every day life and nature, they sometimes showed tints of

theatrical works. Some of the figures in the pictures were seen clad in

theatrical costumes. For example, General Zuo Liangyu in scene 11 and

General Shi Kefa in scene 18 all had four little flags inserted behind

heads. None of the 44 pictures have signatures of the artists on them.

But there are seals with characters of “shao cheng”, “di zhai”, “jian

bai dao ren zhi”. Perhaps they are the studio names or alias of the

artists or painters.

On the last leaf of the album, is an inscription by Yurui, dated “middle

of May in the year Gengwu”, there are also seals with the characters

“si yuan yu rui” and “fu guo gong zhang”. Yurui (1771-1838) was a

descendant of Prince Duoduo (1614-1649), the second son of Prince

Xiuling. He was versatile and well versed in poetry, calligraphy and

painting. The year Gengwu is 1810. It means that the pictures should be

painted before the fifteenth year of the Jiaqing Emperor (r. 1796-1820).

Yurui had not mentioned the names of the artists in his inscription.

This implies that he did not know them at that time but only saw these

pictures. Nor could we imagine the original binding style of the album.

During the years of the Tongzhi Emperor (r. 1861-1875), a man who called

himself Taishousheng copied the librettos of the 44-scene drama in

blue-green, red, black ink on 44 pages with the inscription of “copied

at Liushi zhong lanting jingshe (the Studio of Sixty Kinds of Orchid

Pavilion) in May, summer of the year Guiyou”. From the name

Taishousheng, we could only know that he was a very thin man. The year

Guiyou is 1873. The Studio of Sixty Kinds of Orchid Pavilion was the

studio name of Taishousheng.

Taishousheng put the 44 libretto pages face to face with their

respective pictures and had them mounted into 44 sutra-style leaflets.

Then they were bound into 4 volumes, each with wooden covers at the top

and the bottom. A wooden chip was inlaid in the middle of each of the

top cover. Three characters in running script “tao hua shan (Peach

Blossom Fan)” and two columns of characters in clerical script “For the

pleasure of Ledaozhuren, presented by Taishousheng” were engraved at the

upper and lower parts of the chip. The four volumes were stored in a

diaphanous wooden box which contained an exquisite pedestal and a deep

square cover. Three characters in standard script “tao hua shan” were

carved on the top of the cover. The binding and boxing might be finished

a little later after 1873.

…

The publication of the album of Peach Blossom Fan by the Writers

Publishing House is the first time it is published by a photomechanical

process. The illustrated book contains Kong Shangren’s full text and

summaries of the 44 scenes both in Chinese and English. For the

convenience of readers and collectors, the book is bound in modern

thread-stitched binding style and kept in a cardboard box instead of

sutra binding with wooden covers and wooden box. This binding style is

in conformity with other books of the illustrated series. This edition

could be regarded as a new endeavour to popularize an old treasure. In

recent years, the performance of the kunqu drama of Peach Blossom Fan in

the mainland enjoys tremendous popularity. The publication of the new

edition will certainly add more radiant and more beauty to the

300-year-old peerless masterpiece.

Sample Pages Preview