Our second meeting took place on the weekend, only five days after the first one. Puyi had phoned Mr. Sha Zenxi, inviting us to attend a ball that was to be held at the auditorium of the CPPCC Headquarters(HQ). We accepted the invitation, leaving for the ball in plenty of time. Surprisingly, after getting off the bus and walking for only a few steps, we saw Puyi coming to welcome us, beaming with delight. I felt very content to sense his warm sincerity again. Inside the auditorium of the CPPCC HQ, the band was repeatedly playing “The Friendship Waltz”, with the couples dancing happily. At first, Puyi remained seated by Mr. Sha and me, accompanying us while we sipped tea. Later on, Mr. Sha politely asked a lady to dance, intentionally leaving an opportunity for Puyi and me to talk freely, but it seemed that he couldn’t find a suitable subject to talk about. When, after a regular break, the music started up again, Puyi stood up and , following the example of the other male dancers, invited me politely,saying: “Comrade Li, let’s have a dance,” but he added: “I can’t dance, so I’d like to learn from you. Maybe I’ll make your shoes dirty.” I said: “I can’t dance either!” Very soon, I realized that he really couldn’t dance! He had no idea about rhythm and he couldn’t follow the beat. Sometimes his shining leather shoes trod on mine, which was followed by a gentle voice: “ I’m sorry, ” or an apologetic smile. However, he could follow “the slow step” by meeting my steps, albeit unskillfully. When the music changed to “the quick step”, he immediately got muddled up, so that finally he just simply dragged me around in circles. “You were emperor for so long, why didn’t you learn to dance?” I asked, when we returned to our seats by the small round table. I was perspiring profusely! “Back then, I was the ‘Son of Heaven’, when even my parents had to kowtow to me, when they saw me. Ordinary people were accused of discourtesy if they even dared raise their heads to look at me. No lady was willing to risk her life by dancing with me, or even placing her hand on my shoulder, so it was impossible for me to learn how to dance. Now that I’m an ordinary citizen I hope that you’ll be able to teach me, and make up for lost time,” he stated. Afterwards, he said to me in a whisper: “May I phone you directly, to avoid having to bother Mr. Sha?” He asked for the telephone number of our hospital and I gave it to him. But at the same time I softly explained my concern to him: “You enjoy such a great reputation, it might make it difficult for me to get along with my colleagues in the hospital, if they know who you are.” Puyi smiled: “I won’t say that I’m Puyi. If your colleagues want to know my surname, I’ll just tell them that I’m Mr. Zhou.” From then on, our hospital received more and more telephone calls, asking for me. Many of my colleagues therefore became awarethat I was dating a man called Mr. Zhou. The ball came to an end just after 10 pm. It was extremely cold outside that evening, and a thick layer of ice had formed on the ground. With great care Puyi escorted Mr. Sha and I to the bus stop. When the bus drew up, Puyi again reminded us to be careful when getting on the bus as the footboard was very slippery. I thought to myself that “The emperor” was really good at caring about others.

I am overjoyed that My Husband Puyi is to be published. Aixinjuelo Puyi was the last Emperor of the Chinese feudal society era. He was placed on the throne as Emperor Xuantong at the young age of three, but less than three years later his forced abdication was announced. Afterwards, according to The Articles Provided for the Favourable Treatment of the Great Qing Emperor after his Abdication, decided upon by the Provisional Government of the Republic of China, he was still allowed to live in the inner court of the Forbidden City, acting as an Emperor “behind closed doors”1. For the following 13 years he lived this role, until in 1924, when he was expelled from the Forbidden City by the celebrated Christian General, Feng Yuxiang. Following this, it was arranged that he would stay at the Japanese Concession in Tianjin. In 1932, the Japanese secretly sent him to Northeast China to be the Puppet Emperor of the “Manchukuo”1 set up by Japanese Imperialists. With the final surrender of the Japanese Imperialists in August 1945, Puyi then fell captive to the Russian Red Army, being escorted first to Chits, then to Khabarivsk (two Russian cities in the far east, close to Northeast China), where he was placed under house-arrest for a period of five years. After the establishment of the People’s Republic of China, the Chinese and the Soviet Union Governments, following bilateral talks, finally decided to extradite Puyi back to China. Puyi was then detained for ten years at Fushun War Criminals Prison2, located in Northeast China. He was reeducated and remoulded there, through physical labour and being imbued with Communistic ideas. Finally Puyi realized his wrongdoing, so repented for his role in aiding the Japanese Imperialists in enslaving the people in Northeast China. He started a new life, with a completely different outlook, which resulted in him becoming an honorable, respected citizen of the New China, and my good husband.

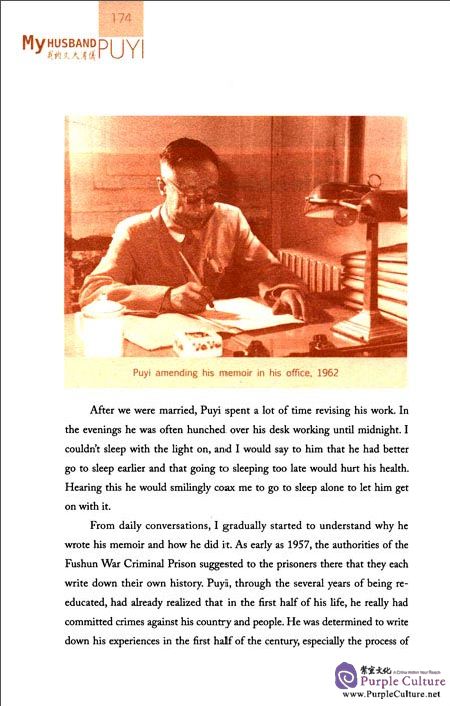

His autobiography The First Half of My Life - from Emperor to Citizen has been popular at home and abroad, as a book which has continued to rivet the world’s attention, since it was published in 1964. Now, to the reading public who are interested in Puyi, I’d like to present with this book, My Husband Puyi which is about his new life, after being granted special amnesty in 1960. He enjoyed this new life for only eight years, as he died of kidney cancer in 1967. Eight years is a much shorter period compared with the first half of his life which lasted for more than fifty years, but much more valuable, if viewed in the light of his life’s significance. Puyi and I had been married for five and half years, but if taking into account from the day we were introduced to each other, we were together for almost six years. We were fortunate to have experienced a sweet courtship, a happy home life and our attendances to each other when we were both ill.

In 1984, the first edition of my memoirs, Puyi and I was published, creating a major sensation in China. In its preface, I explained how I came to write the book, as follows: I remember that it was in September of 1979, when Mr. Wang Qingxiang, an historian from the Historical Research Institute with the Jilin Provincial Academy of Social Sciences, paid a visit to my home. He urged me to write the memoirs of my husband, for he believed that it would prove to be a great contribution to our Chinese nation. The principle we agreed on was that I should write down every event and sentence as they came to my mind, and that he would help me to draw out my memories to the greatest extent possible. He said to me “Your memoirs must be first-hand data as precise as possible. They will be an invaluable document for historical research. So every single word of it must conform to historical facts.” I also held this view. My memoirs were written intermittently during a period of six months. Whenever I thought of the past, I relived the memories of the life that we had spent together more than ten years earlier. It had been as though my husband was standing lifelike in front of me, when the reminiscences flooded back to me. I have no idea of how many times I laughed while savouring the happiness and sweetness of that time or how often the tears suddenly welled up in my eyes, due to the sadness of losing him. My memoirs may not be perfect but I’m confident that they are realistic. While helping me with the compilation of my memoirs, Mr. Wang Qingxiang reiterated that his desire was to make an accurate historical record and that he preferred to omit any unclear details, where my memory failed me. My original memoir, Puyi and I is the result of our mutual cooperation. First, he collated my oral accounts by cross-referencing them with the manuscript left by Puyi. Then, he came to Beijing to go over every single word and sentence together with me. I’m glad that the final text successfully conveys the essence of my spoken accounts. Of course, my memoirs mostly show Puyi’s home life. They obviously couldn’t cover every aspect of the second half of his life. In order to get a well-rounded view of citizen Puyi, my memoir should be read alongside Puyi’s own diary and articles, which were written during this period, to supplement your understanding.

Twelve years later, Mr. Wang Qingxiang and I again worked happily together to thoroughly revise Puyi and I by adding to it with many more details of our common life. My difficult experiences during the Cultural Revolution as Puyi’s widow significantly contrasted with my improved life and situation in the new era. By 1978, China had begun to implement the progressive policy of reform and was opening up its doors to the outside world. During the previous ten years, more and more Chinese and foreign reporters, historians, readers of my book, tourists and personalities of various circles had come to visit me. These visits greatly helped me with my book revision and they also aroused again affection and love for my dear husband. These foreign reporters had often laden me with various questions about our courtship, marriage, our daily life and work, our tours, our times in hospital, as well as the relationships between Puyi and some members of the former Aixinjuelo Royal Clan and also between him and the State Leaders. To answer their questions adequately, I used to write down the key points as I remembered them. Later on these recollections naturally became useful material for the revision of my former memoirs. I named the revised book My Husband Puyi, hoping that it might convey my affection for my dear husband. Finally, I’d like to express my gratitude to all the friends who have helped me, as well as the readers who will enjoy the reading of this book.

Li ShuXian (1924-1997)

September 23rd, 1996